Human trafficking is a complicated issue. When explaining it, we often talk about how victims were deceived, and the exploitative situations they were forced into. But there is one key part that is rarely discussed: Just who are the traffickers?

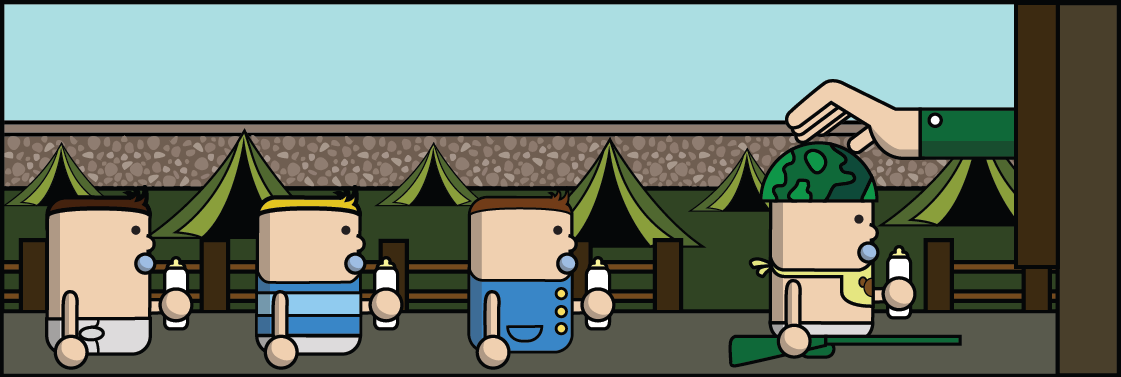

Understanding who human traffickers are and what their motivations are can help us to better grasp the issue. Essentially, anyone who contributes to the trafficking of a person and has the intent of exploiting a victim is considered a trafficker.[1] This definition can apply to a wide array of people such as recruiters, transporters, employers and even sometimes those who provide travel documents or corrupt officials.

Another group that is involved in the process are the intermediaries; these are the people who take care of tasks such as identifying when and where to cross borders, bribing border guards or even keeping watch over the victims. Intermediaries are regarded as traffickers as they assist in the trafficking and exploiting the victim. While traffickers can sometimes be involved in all parts of the trafficking process, they are usually only involved in one step of the process.[2]

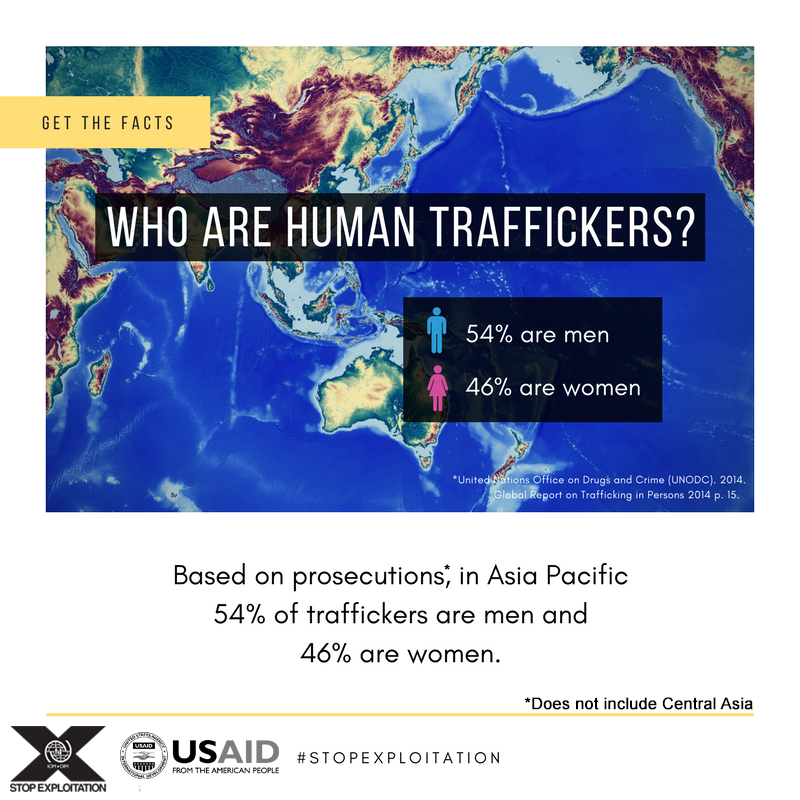

People often associate trafficking as a crime that is primarily committed by men, however figures from prosecutions in Asia Pacific show that around 46% of traffickers are women.[3] Women can appear more trustworthy to children and women, which is why they are often the ones who act as recruiters. Traffickers have been known to use belonging to the same ethnic group as a way to garner the trust of their potential victims. Sharing a common language and culture allows traffickers to better understand the motivations and fears of their victims, making it easier to exploit them. While victims from Asia are trafficked globally, the traffickers of these victims commonly come from the same country, province or community.

Human trafficking is one of the most lucrative illegal businesses in the world with estimated annual profits of over US$150 billion a year.[4] In Asia Pacific alone, traffickers make around US$52 billion in profits each year.[5] Clearly, the primary motivator to traffic people is money. Sometimes extreme poverty can lead people to traffic their own family members, such as cousins, sisters or daughters. However, the range of educational and social status of human traffickers is wide.

While some traffickers are uneducated and impoverished, others have an education and a regular income. All kinds of professionals, including lawyers, doctors, policemen, politicians, mechanics and chefs, have been found guilty of people trafficking. Unfortunately even those who were trafficked themselves can turn into traffickers for various reasons. Some former victims become traffickers due to a lack of skills, while others are forced by their exploiters to recruit and traffic more victims. This can blur the lines between traffickers and victims.[6]

To learn more about what human trafficking is and the processes involved, check out our “How to explain human trafficking to your friends and family” blog.

[1] United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). 2009. Training Manual to Fight Trafficking in Children for Labour, Sexual and Other Forms of Exploitation p. 31.

[2] United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). 2009. Training Manual to Fight Trafficking in Children for Labour, Sexual and Other Forms of Exploitation p. 31.

[3] This statistic does not include prosecutions in Central Asia. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2014. Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2014 p. 77.

[4] International Labour Organization (ILO). 2014. Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour p. 13.

[5] Ibid.

[6] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2008. Workshop: Profiling the Traffickers p. 5-6.