Month: January 2017

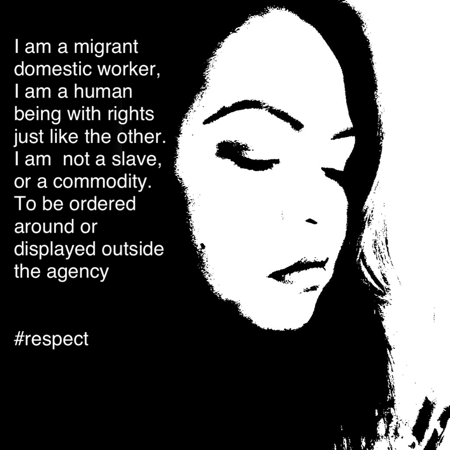

My Poem, My Voice

By Robina Navato

I have been working here in Singapore for almost 21 years. And I can say that I am blessed enough to have worked with very good families. From my local employer of 11 years who treated me like a part of their family, to my amazing American employers. Life was not easy at first but I managed to adjust.

Unfortunately, it’s not that easy for many other domestic workers here. It breaks my heart to know their situation, how they are abused.

Seeing how many of my fellow migrant workers are mistreated motivated me to become a volunteer at HOME (Humanitarian Organization for Migrant Economics). I am part of the Help Desk, where I give advice to distressed domestic workers and help them solve problems with their employers. It is really easy for me to put myself in their shoes, to imagine what they go through. Sometimes, I get affected too, especially when I see them cry.

Witnessing our struggles, I turned to poetry to speak out against abuse. My poems became my voice. I wanted our voices to be heard.

When I started writing my first poem, “Cry of the Hidden”, it took less than a day. It is a poem about the lives of two domestic workers I’ve known. From there I wrote “Sacrifice,” which reflects my own experience. I dedicate it to all the migrant mothers who left their families with the hope of providing a better life for their children. As it turned out, this wasn’t as easy as we thought.

Life is tough for migrant domestic workers. We made a huge sacrifice in leaving our families, especially our children and we wish our employers—especially those who are parents themselves—would empathize with what we go through. We move thousands of miles away from home because we want to provide for our families too. Respect our rights.

Be Smart

What is human trafficking?

Changing perceptions about migration

By Dana Graber Ladek

No matter how you look at it, migration is a journey, and this is a good time of year to think about migratory journeys, as many of us – particularly foreigners like me – have made long journeys back home to visit loved ones.

International Migrants’ Day is marked on 18 December each year because on that day in 1990, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.

This is a particularly special time for IOM to be celebrating migration with you. On 19 September, we became a United Nations agency, and on 5 December we celebrated our 65th birthday. In addition, 2016 marked 30 years since Thailand became an IOM member state.

To mark this important year and International Migrants Day, IOM held a Global Migration Film Festival in December. This festival aimed to change negative perceptions and attitudes towards refugees and migrants, and to strengthen the social contract between host countries and communities, and refugees and migrants.

Changing perceptions about migration is an extremely important aim, and I would like to look at what is happening in our world right now to explain why.

We are peering into a world in tumult and crises. The effects of climate change, the increasing frequency of disasters, and the emergence and reemergence of killer diseases are constant threats. Society at large seems to be reacting by voting in a different sort of leadership, one that promises tough, firm action, at the expense of migrants.

So now more than ever it is important to embrace, rather than resist, the inevitability of migration. We need to change the perception of migrants among our public and better integrate migrants in our societies. Most migrants simply want an opportunity to improve the lives of their families back home.

IOM, the UN Migration Agency, today calculates that one in every seven people on our planet is a migrant – someone living, working and starting a family somewhere other than his or her habitual place of residence. And, even though so many are just trying to live, too many are dying on their migration journey.

IOM’s Missing Migrants Project attempts to identify every dead, missing or “disappeared” migrant in the 165 countries where we operate. In 2016, for the third straight year, the Missing Migrants tally will top 5,000 fatalities.

Think about that: every day for the past three years, a dozen migrants have died, on average, or one man, woman or child every two hours.

And these are only the fatalities that we know about. Many more deaths go unrecorded by any official government or humanitarian aid agency.

Along with our sorrow and our shock at these deaths, we must recognize that migration is the mega-trend of our time. It’s a mega-trend which has pushed migration into the public’s consciousness and to the top of every government’s agenda. It is also a trend that contributes greatly to society – migrants promote economic development. They build the apartments we live in, they take care of our children and elderly, they pick the fruit we eat, they sew the clothes we wear.

With the right support, those migrants who stay will contribute to whatever society they settle in, whether it is economically or culturally. Therefore, it is important that partnerships are built between migrants, host communities and governments to nurture the benefits of their presence in the country.

As we commemorate International Migrants Day, let us recognize that we have enough opportunity for all – we need only to share it.

Dana Graber Ladek is Chief of Mission of IOM Thailand. She has spent most of her adult life living and working outside of her home country, the U.S.

A Culture of Migration

With 59 million (documented) migrants from the Asia-Pacific region moving beyond their national borders, it is important to understand what drives people. While researching the attitudes of migrants, particularly what motivates them to migrate, the same theme of poverty and hopes of a better job kept coming up. However, in a region where migration is so common, there must be more than economics that pushes people to migrate. Then I turned to some anthropological accounts that discuss migration as a cultural phenomenon, as a journey that people embark on in order to ‘find their luck’.

One author, Filomeno Aguilar, compares migration to a rite of passage; he parallels migration to a journey of finding oneself. When migrating, people leave being their lives and their identity. They start a new life in a new place, somewhere where they have no past and usually don’t know anyone. Aguilar portrays migration as very difficult, not only emotionally because you uproot your life, but also physically as migrants often endure tough jobs that are physically demanding. But why do people embark on such a journey? Aguilar suggests it is because people try to prove their independence, or try to make a better life for themselves, or they try to find their luck.

Another Filipino author, Naiomi Hosada, discusses this concept of finding one’s luck in more detail. She studied Filipino migration and comes across the cultural phenomenon of suwerte, or luck. Hosada describes this idea of finding one’s luck as a cultural motivator for migration. Luck in this sense is not something that falls in your lap; its something you have to seek out. Similar to what Aguilar describes, Hosada talks about going on a journey and facing risks, like working in dangerous and difficult conditions. However, working hard and facing risks doesn’t guarantee finding suwerte. It is something that is granted from above. It is also interesting that luck does not necessarily mean finding wealth. Luck can also come in the shape of a strong personal connection, like finding a good employer or spouse.

Migration can be one-way or circular. For example, in Indonesia — especially in Minangkabau culture — the concept of merantau denotes the act of leaving one’s home for economic opportunities abroad or across the country. Often times, those who merantau settle permanently in their new home. In contrast, migration can also be circulatory; Aguilar’s migratory rite of passage concludes with returning home to share one’s wealth and experiences. Migrants act as a source of inspiration or wisdom to others in the community. Hosada also touches upon this act of coming home. Migrants need to return to share their suwerte. If their luck isn’t shared, it can be lost. Therefore, migrants usually return to their community or family bearing gifts.

In a region where labour migration is so common, it is essential to understand what inspires people to migrate. Clearly, the hope of a better life with a better job is the most important motivator. Yet, as these anthropological studies show, migration can be more than just economics. As the culture of migration has become so imbedded in our societies, it is important to look at how different culture perceive migration in order to better understand what drives us.

Sources:

Hosoda, N. Connected Through “Luck” Samarnon Migrants in Metro Manila and the Home Village. Philippine Studies. 2008. 56(3).

Aguilar, F. Ritual Passage and the Reconstruction of Selfhood in the International Labour Migration. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 1999. 14(1).

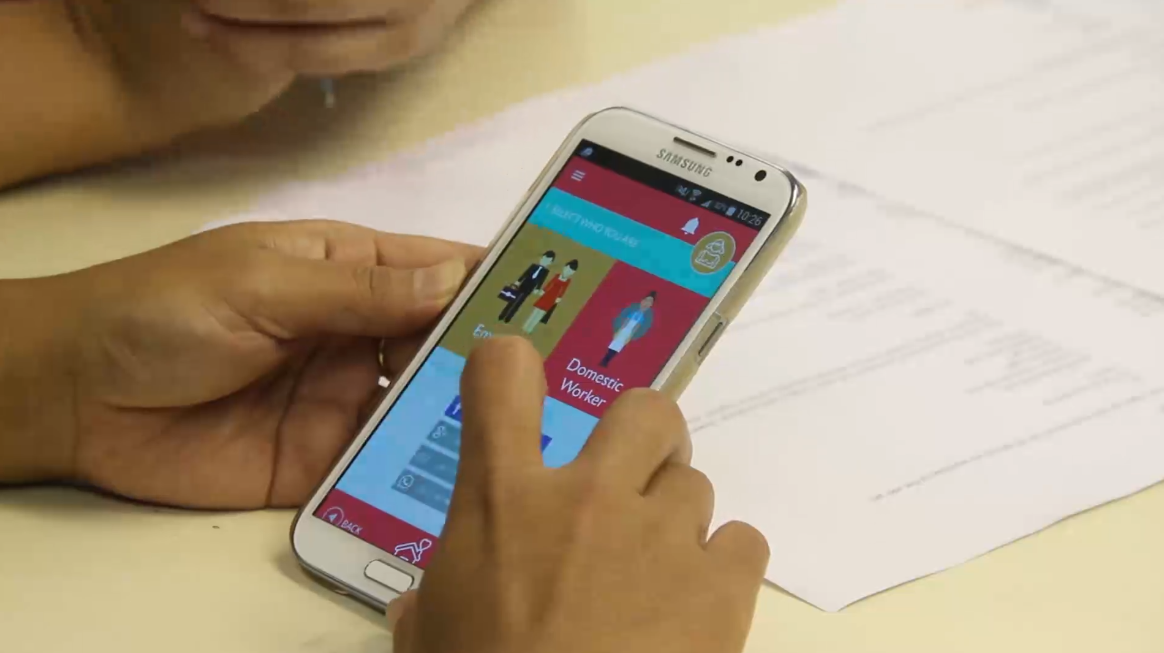

IBM and IOM prototype game-changing mobile app to help domestic workers.

“Oh, this could be useful!”, says Champa (34) a migrant domestic worker from Myanmar while looking at the phone she is holding. “This can help domestic workers communicate more easily with their employers – and this is so important to prevent tension in the first place”. She briefly looks up and smiles; a brief moment that is broadcast live via video feed into a room only 20 meters from where she is sitting. Champa knows that her reactions are observed by a panel. A total of 14 experts from the International Organization for Migration, IBM and HomeNet, a domestic worker network based in Thailand, are watching her every move. They are there to understand how testers reacts to the mobile app’s prototype they had developed together. 1700 km to the east, Tatik Samidi another migrant domestic worker in Hong Kong investigates another feature. “Take a photo of my important documents?”, she says. “Are we going somewhere?” – the room erupts with laughter. This feature won’t make it into the final app.

The initiative is part of a collaboration between the International Organization for Migration’s IOM X programme, a media campaign and innovations programme to help prevent exploitation and human trafficking, and IBM’s Corporate Service Corps (CSC) programme. The latter deploys IBM staff from different countries to volunteer with government and non-governmental organizations in order to solve critical problems while providing IBM employees with unique leadership development opportunities. This time, they were sent to help IOM X answer the following question: Can IOM develop a mobile app that is useful, widely used and most importantly helps prevent the exploitation of domestic workers in ASEAN?

Champa moved to Thailand more than 23 years ago. She is one of over 53 million domestic workers worldwide who are employed in other’s private households. Employment as a domestic worker is one of the main opportunities for women who migrate within Asia Pacific; but this form of employment also leaves many women vulnerable to exploitation. An estimated 1.9 million domestic workers in Asia Pacific are being exploited. Reported exploitation includes low pay or no pay, excessive working hours (such as being on call for 24 hours a day), no weekly day off, living in poor and unsafe conditions, inflated agency fees, debt-bondage, forced labour and forced confinement.

“Female migrant domestic workers face a triple vulnerability to exploitation: being a woman, a migrant and a domestic worker. Lack of rights, the extreme dependency on an employer and the isolation and inspected nature of domestic work add to their vulnerability.”, says Nurul, Head of Sub Office IOM HK who has worked with Philippino and Indonesian domestic workers for more than 8 years. “At IOM X we are always looking for innovative ways to use media and technology to help prevent exploitation. For us we didn’t want to develop an app because it’s the trendy thing to do. Our research has shown that a significant proportion of migrant workers from Southeast Asia, including those from poor and rural backgrounds, use computers and have smartphones. As access to the internet increases and the technology costs continue to decline, mobile technologies appear to represent a uniquely suitable intervention vector to directly address vulnerability factors related to the exploitation of otherwise isolated and exploited female domestic workers. And this is where our partnership with IBM can help”, says Tara Dermott, IOM X’s Team Leader.

Over the course of five weeks, the Fortune 500 company’s employees worked with IOM X to learn about the issue, interview experts, develop a prototype, test its assumptions with domestic workers in Thailand and Hong Kong and refined test results into technological specification, a go-to-market strategy and business plan. “The context in which domestic workers are required to perform is different from traditional work environments. Not only are employers and employees required to get used to and manage their expectations on each other, they also struggle with language barriers, cultural differences and gender dynamics. Employers we interviewed highlighted that this may lead to tension between employers and domestic workers. While many employers treat their employees with dignity, some relationships turn sour, result in built up frustration, negative treatment and sometimes exploitation of the domestic worker. Add to this a power dynamic that favours the employer, and domestic workers often end up isolated with their access to support and even technology itself depending on whether the employer allows it. As such, a truly effective solution must take both, the employer and employee into consideration.” says Helvio, a Technical IT Architect with IBM.

It was due to this level of protracted complexity that IOM X chose to structure the project a little bit differently. Borrowing from the Design Sprint method, an agile development framework straight out of Silicon Valley, experts from more than five countries and four sectors worked together in order to dissect the issue, develop solutions and test them in the first week of IBM’s involvement. “We wanted to move away from those run of the mill brainstorming sessions.” says Mike Nedelko, IOM X’s Digital Product & Outreach Manager. “For us it was important that everyone in the room became an expert on the problem before putting forward solutions. It was a truly inspiring project to work on. The IBM volunteers hit the ground running. By the end of the first week, we had IT professionals discuss international development frameworks and social workers sketch App UIs. This project was a true communion of expertise. Something we haven’t seen in the area of public private partnerships up to this point and we are convinced that the ideas resulting from this partnership will be ground-breaking”.

Both IBM and IOM X are carefully guarding exactly what it is this app will do to help prevent the exploitation of domestic workers. “All we can say at this point is that it will be a truly useful solution to both employers and domestic workers. The benefits for domestic workers are all there, but where it gets really exciting, are the reasons employers will want to use it, how this will empower their employees and change the ways domestic workers and employers communicate with each other, not only in ASEAN but around the world.” adds Mike. “What we have at this stage is a great and commercially viable idea that is self-funding, supported by an extremely strong business plan and go-to-market strategy. For now, we ask you to watch this space. We need time to develop this further; but this could be a real game changer.”

Behind open doors

At the May 2016 press launch of Open Doors: An IOM X Production, an Indonesian woman came up to me and said, “This is really good. It is so good to see positive stories, rather than negative ones, used to teach a lesson”.

The woman, who had previously worked as a domestic worker in Hong Kong, went on to tell me that, although it is important for news media to report on how domestic workers are being mistreated and exploited by their employers, these kind of stories sometimes further influence how employers treat their domestic workers as lower class citizens because they think it’s the norm. She said that stories of respect and professionalism between the employer and the domestic worker need to populate media too, in order to make these stories the norm, and to make this type of work relationship ‘cool’.

IOM X is always on board to help make something look cool, positive and empowering. Research has shown that raising awareness about risks, or negative messaging like ‘don’t do this, don’t do that’ are not very effective. An overly negative campaign will erode trust from your target audience[1]; it will leave them feeling alienated or discouraged, rather than motivated.[2] The mistreatment of domestic workers is not new, but like many other organizations advocating for the fair treatment of domestic workers, IOM X embarked on the challenge to change how we talk about domestic workers for the better: “Do this, do that!”

Open Doors: An IOM X production is a long-form video that follows three different stories of migrant domestic workers working in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. The video aims to encourage employers to respect and treat their domestic workers fairly. To assess its effectiveness, IOM X hired research agency Rapid Asia to conduct an impact assessment in Thailand and Indonesia with 600 people, including employers of domestic workers and the general public. In both countries, people who identified as employers of domestic workers represented nearly 50% of the respondents.

In Thailand, interestingly, employers who hire Thai domestic workers and those who hire migrant domestic workers recorded very different results. All employers recorded positive intention to treat domestic workers fairly; negative attitudes (such as ignorance discrimination) were more prominent amongst those who hire Thai domestic workers than those who hire migrant domestic workers. This could be explained by pervasive negative attitudes in Thailand toward migrant workers in general. These findings clarified that, although the video is an effective tool in raising awareness about domestic worker rights and maintaining positive behaviours, IOM X should continue to do research and produce content that address negative attitudes towards migrants workers.

The lesson learned in Indonesia is that, even after watching Open Doors there still seemed to be gaps in knowledge of, and attitude towards, fair working hours. The survey found that 80% of employers do not think that live-in domestic workers should decide how to spend their free time and 50% of employers do not give their domestic workers one day off per week. This indicates that a majority of employers think that domestic workers should be available to work at any time, especially if they are live-in, regardless of how many hours they have already worked in a day or week. This would also explain why there was some confusion around the message of “one day off”; some respondents did not understand fully whether it was one day off per week or time off as needed for extenuating circumstances. The video proved to be an effective tool to raise awareness about the exploitation of domestic workers and promotion of their rights, however, in the future, IOM X will consider creating content/activities that specifically target Indonesian audiences and address the issue of “time-off”.

Changing the conversation from negative to positive in terms of highlighting the positive contributions that domestic workers bring to families and society is not easily achieved with one video. However, Open Doors did take a step in the right direction. In Indonesia, 91% of viewers took at least one step towards the desired behaviour change of respecting domestic workers rights. In Thailand, more than half of the viewers said they learned something new and would speak to others about the issue of domestic worker rights.

Read IOM X’s full Impact Assessment of Open Doors:

Download Thailand report

Download Indonesia report

Know your audience: Prisana Impact Assessment

Getting the message right takes more than a group of communication practitioners. You need to go to the experts: those to whom the message is intended.

When IOM X develops videos, it conducts consultations with people from its target audience. For Prisana: An IOM X Drama, IOM X invited a group of young people to get together and talk about the fishing industry.

During the discussion, it emerged that all of the participants ate seafood almost every day. However, when asked if they knew where this seafood actually came from, nobody had an answer – except that the fish most likely came from the sea. Most of the participants thought the fishing industry was dominated by private family businesses, when in reality small-scale operations like this cannot satisfy our insatiable appetite for seafood.

The group was asked to think about what it is actually like to work on a boat. They recognized that this work is tough; they said fishermen have to work all the time, there is nothing to eat, wages are low, it is dangerous, they are likely to suffer accidents, they are separated from their families and can be cheated by their employers. One of the participants pointed out that fishermen are probably afraid of quarreling with the boat owner because he could easily harm them.

IOM X then asked the group if they thought that human trafficking happens in the fishing industry. Surprisingly, the answer was no.

Despite the fact that they had just described conditions of labour exploitation on fishing boats, the young people were surprised to learn that is in fact human trafficking. In their eyes, human trafficking is something that only happens to women and girls in the sex industry. They didn’t associate manual labour with human trafficking, or recognize that men and boys could be victims.

Working together with Thailand’s most famous on-screen couple, Mario Maurer and Mai Davika Hoorne, and superstar actor/producer Ananda Everingham, IOM X used its findings from the group discussion to develop Prisana: An IOM X Drama. The emotional video tells the story of a photojournalist who helps a migrant woman find her husband, who has been trafficked onto a fishing boat.

To test whether Prisana accomplished its goal of raising awareness about human trafficking in the fishing industry, and inspiring young people to learn more about the issue, IOM X surveyed 100 Thai nationals before and after watching the video.

The results showed that Prisana is a great tool to help raise awareness on human trafficking in the fishing industry. Participants felt the drama is excellent at making viewers feel concerned about trafficking victims and encourages people to learn more about the subject.

Prisana also helped to strengthen positive behaviours that help prevent trafficking and labour exploitation as 64% of viewers said they would support fishing companies that follow fair practices. Additionally 52% of those surveyed said they would speak to others about human trafficking in the fishing industry.

While Prisana was successful at raising awareness and encouraging people to take positive actions to help prevent exploitation, the video was not particularly successful at shifting negative attitudes towards migrant workers in the fishing industry. However, this result did not come as a surprise; changing attitudes is extremely difficult and is unlikely to be accomplished through a short video. Unfortunately such negative attitudes exist not only in Thailand but are pervasive across the region and around the globe.

Changing people’s perceptions and attitudes is difficult and takes a long time and continued exposure. But if successful, a change in perceptions and attitudes can inspire behaviour change that can make a real difference in the lives of those facing labour exploitation. The key is working with your target audience to get the message right.

Power by

Power by