A Culture of Migration

With 59 million (documented) migrants from the Asia-Pacific region moving beyond their national borders, it is important to understand what drives people. While researching the attitudes of migrants, particularly what motivates them to migrate, the same theme of poverty and hopes of a better job kept coming up. However, in a region where migration is so common, there must be more than economics that pushes people to migrate. Then I turned to some anthropological accounts that discuss migration as a cultural phenomenon, as a journey that people embark on in order to ‘find their luck’.

One author, Filomeno Aguilar, compares migration to a rite of passage; he parallels migration to a journey of finding oneself. When migrating, people leave being their lives and their identity. They start a new life in a new place, somewhere where they have no past and usually don’t know anyone. Aguilar portrays migration as very difficult, not only emotionally because you uproot your life, but also physically as migrants often endure tough jobs that are physically demanding. But why do people embark on such a journey? Aguilar suggests it is because people try to prove their independence, or try to make a better life for themselves, or they try to find their luck.

Another Filipino author, Naiomi Hosada, discusses this concept of finding one’s luck in more detail. She studied Filipino migration and comes across the cultural phenomenon of suwerte, or luck. Hosada describes this idea of finding one’s luck as a cultural motivator for migration. Luck in this sense is not something that falls in your lap; its something you have to seek out. Similar to what Aguilar describes, Hosada talks about going on a journey and facing risks, like working in dangerous and difficult conditions. However, working hard and facing risks doesn’t guarantee finding suwerte. It is something that is granted from above. It is also interesting that luck does not necessarily mean finding wealth. Luck can also come in the shape of a strong personal connection, like finding a good employer or spouse.

Migration can be one-way or circular. For example, in Indonesia — especially in Minangkabau culture — the concept of merantau denotes the act of leaving one’s home for economic opportunities abroad or across the country. Often times, those who merantau settle permanently in their new home. In contrast, migration can also be circulatory; Aguilar’s migratory rite of passage concludes with returning home to share one’s wealth and experiences. Migrants act as a source of inspiration or wisdom to others in the community. Hosada also touches upon this act of coming home. Migrants need to return to share their suwerte. If their luck isn’t shared, it can be lost. Therefore, migrants usually return to their community or family bearing gifts.

In a region where labour migration is so common, it is essential to understand what inspires people to migrate. Clearly, the hope of a better life with a better job is the most important motivator. Yet, as these anthropological studies show, migration can be more than just economics. As the culture of migration has become so imbedded in our societies, it is important to look at how different culture perceive migration in order to better understand what drives us.

Sources:

Hosoda, N. Connected Through “Luck” Samarnon Migrants in Metro Manila and the Home Village. Philippine Studies. 2008. 56(3).

Aguilar, F. Ritual Passage and the Reconstruction of Selfhood in the International Labour Migration. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 1999. 14(1).

Editor’s choice

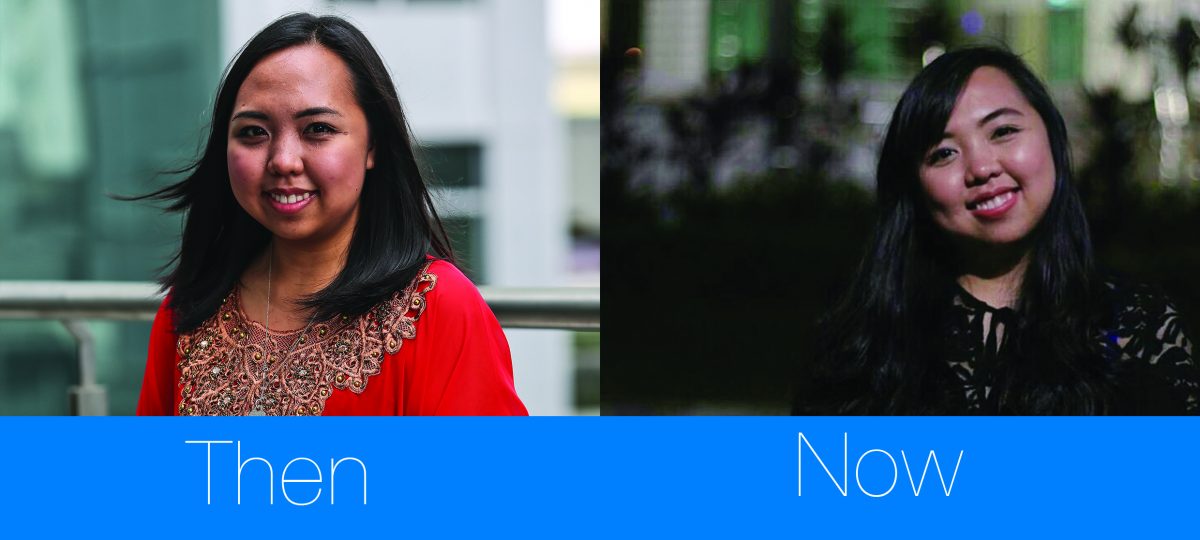

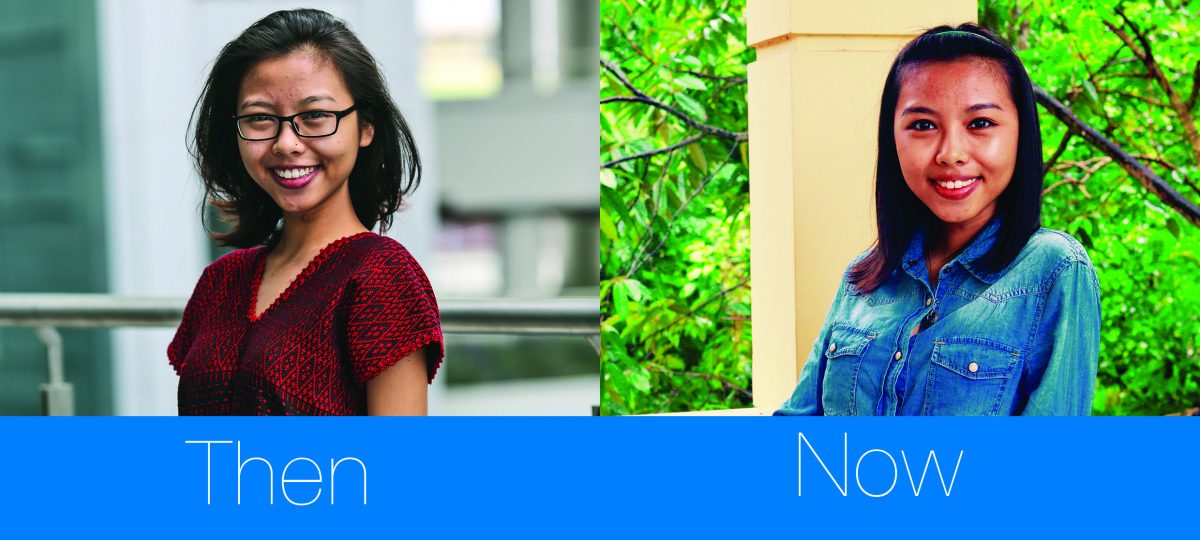

Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

In 2015 when IOM X was just a few months old we brought together 20 youth leaders from all 10 ASEAN countries in Bangkok for the IOM X ASEAN Youth Forum. The goal was to connect with amazing young people who were passionate about social change and the issue of human trafficking and to share … Continue reading “Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines”

Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

In 2015 when IOM X was just a few months old we brought together 20 youth leaders from all 10 ASEAN countries in Bangkok for the IOM X ASEAN Youth Forum. The goal was to connect with amazing young people who were passionate about social change and the issue of human trafficking and to share … Continue reading “Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines”