Rescued from One Facebook Message

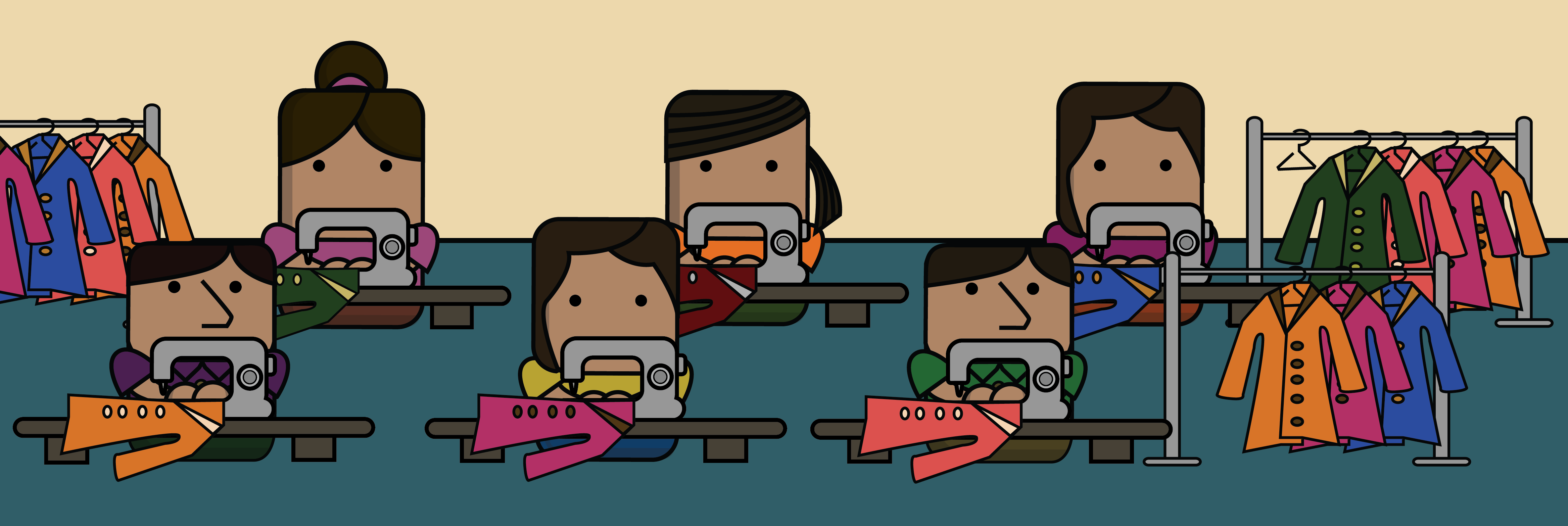

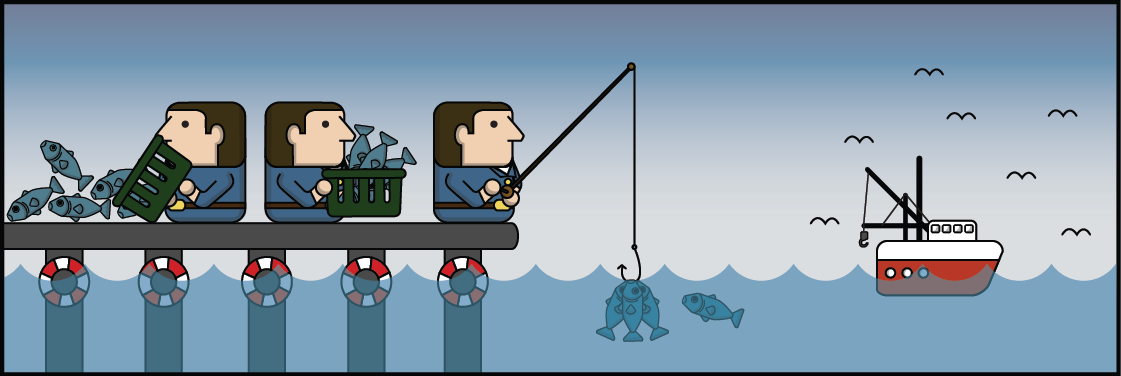

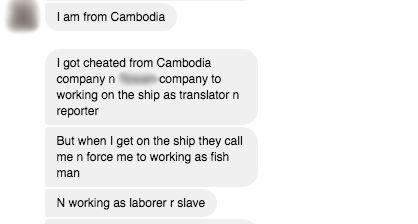

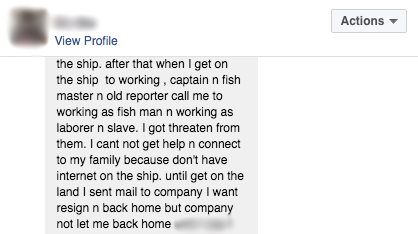

Can social media help rescue victims of human trafficking? It might sound unbelievable, but recently we told you about Pisey¹, a distressed Cambodian man who contacted us on Facebook. Recruiters promised him a job aboard a foreign fishing vessel as a translator, but he soon found that he was being forced to perform hard labour, completely changing up what was agreed to in his contract.

Now stuck at port in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, the fishing company wouldn’t let him go home without paying US$4,000. He was isolated, stranded on a small island thousands of miles away from his family in Cambodia.

In this world of likes, retweets and hearts, social media can feel like a bunch of noise, even fluff. Social media isn’t always the most “inspiring” communication outlet, but it is organic and it does capture real, live conversations. When put to good use, the likes of Facebook, Twitter, and Line can be powerful forces for change.

When Pisey first contacted us on Facebook, we could sense that this wasn’t the kind of message we normally receive — nor was it a hoax. We immediately got in touch with IOM Micronesia — as he was stranded in the Marshall Islands — and they and local law enforcement were able to cross-check the details of his story. Logs showed that his ship had indeed docked at this port, and his description of the surroundings matched up with real places.

Now that he wanted to go home due to violation of his contract, the vessel had left him behind, claiming he would have to come up with US$4,000 to get back to Cambodia.

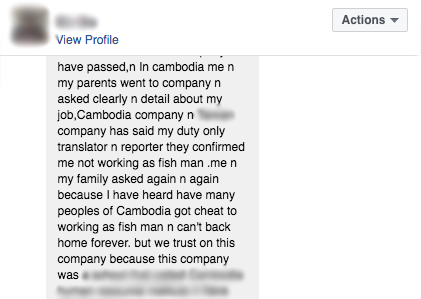

You might be thinking, “How could this happen?” With stories of Cambodians being exploited on foreign fishing vessels dominating the headlines, surely he knew this was risky, right?

In fact, he did.

He and his family were aware of the danger, and they tried to ensure that he received a clear, fair contract. They even tried to find a reputable recruitment agency. Despite taking these precautions, he still fell victim to abuse.

In this case, Pisey was lucky to find a small shop on the island with Internet from where he could communicate with us. After verifying his location and checking that he had freedom of movement, law enforcement met with him to get more details. It turned out that he was truly stuck; the company was holding his passport — an indicator of forced labour. Fortunately, once law enforcement contacted the company, Pisey’s passport was immediately returned to him and he was soon booked on a flight back to Cambodia. Finally, he was going home.

Pisey’s story has a happy ending, but it also reflects gaps in protection for workers on fishing vessels. He was incredibly lucky to find Internet access on land and have the knowledge of how to get in touch with us for help.

Yet, he did not have any means of communication with the rest of the world aboard the ship, meaning he could not report the abuse until it docked. As many fishing vessels — especially those involved in illegal fishing — practice at-sea transshipments, this allows ships to avoid port controls and docking to let off workers. This isolation and lack of connection to the outside world makes workers extremely vulnerable to abuse.

In Pisey’s case, social media facilitated a quick, coordinated response between IOM and law enforcement, and we’re thankful that he was able to go home. But to stop exploitation in its tracks, we need to be developing a worker-driven reporting system that can be used at sea.

It is this access to communication, the building of a network that can act as a safety net, that is truly going to help workers in times of need.

To view country-specific helplines to report suspected human trafficking cases, please visit IOMX.org/FindHelp

To learn more about the exploitation of Cambodian men in the fishing industry, please visit IOMX.org/Fish and http://features.iom.int/stories/marked-men/

¹Name changed to protect identity.

(English) Editor’s choice

(English) Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

sorry not available!

(English) Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

sorry not available!