Who is making your stuff? A look at labour exploitation in supply chains

Stories of labour exploitation make headlines time and again. It seems that forced labour is in almost every product – shoes made in factories where workers labour 18 hours a day with meagre salaries and no overtime pay, clothes sewn by children who are not attending school, batteries for phones made with minerals extracted in conflict zones by people who see none of the profits. Unfortunately there is no certainty that the clothes we are wearing, the shoes on our feet and the cell phone in our pocket are not affected by this problem.

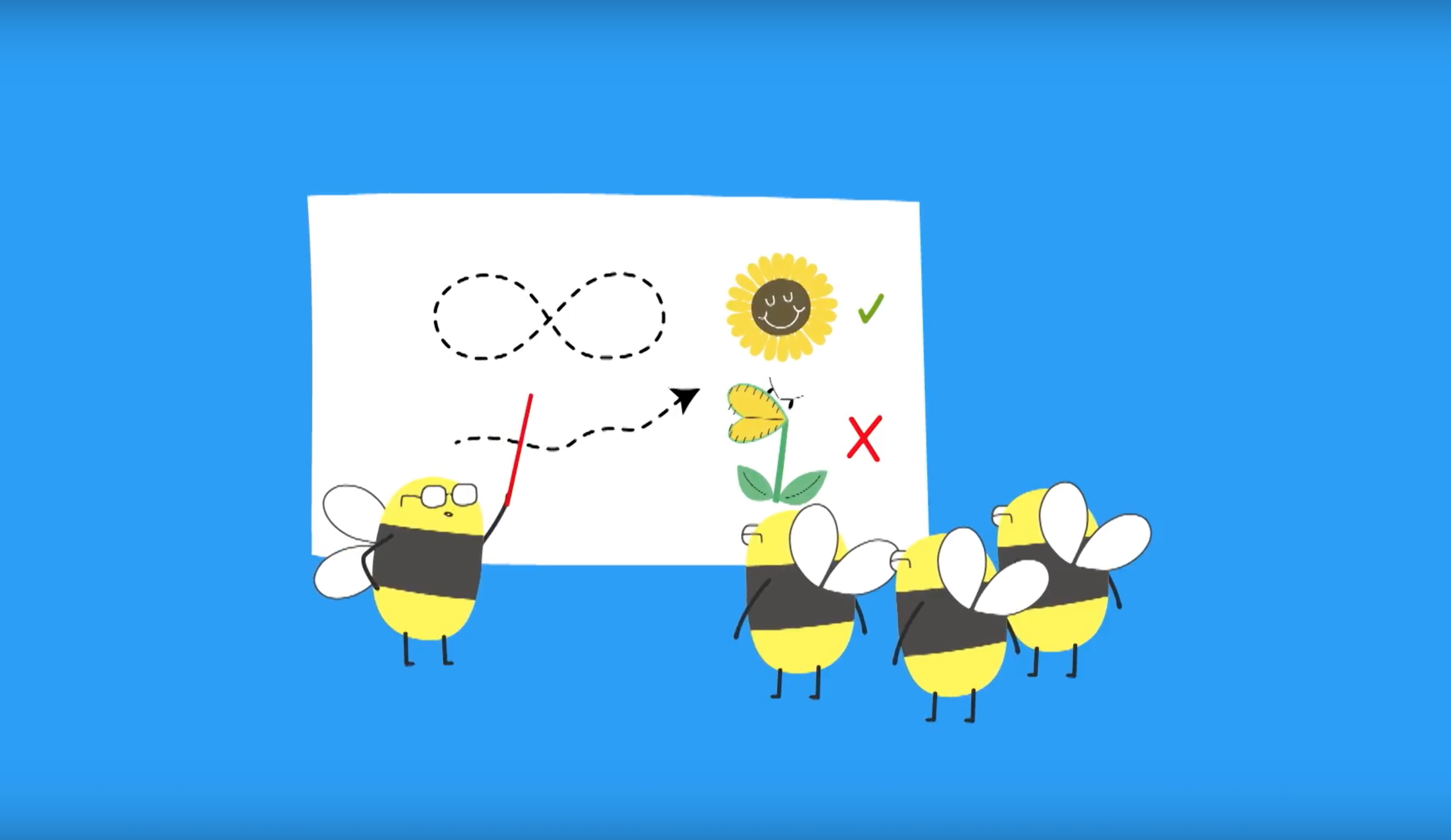

Companies usually are not purposefully producing their products with forced labour. The problem is that companies’ supply chains are extremely long and complex, making them difficult to oversee. Take for example, the bed sheets you sleep on; first, the cotton must be planted and picked. Next, the raw cotton is sent to spinning mills where it is turned into fibre. After that, it is processed into fabric. This fabric is then sent to a factory where it is cut and sewed into a final product. Until the bed sheet reaches the consumer, the materials to produce it have travelled thousands of kilometres and were processed by countless pairs of hands. There could potentially be labour exploitation in every one of these production steps as it is difficult for the company that sells the sheets to keep track of every worker involved.

The company that sells the bed sheets does not typically own the fields where the cotton is grown, or the factories where the raw material is turned into fabric. Companies are also unlikely to own the factories that create the final product. Instead, suppliers (usually in developing countries) are contracted to produce certain goods. These suppliers are in charge of hiring their own workforce.

The people who are employed in these types of factories are usually low-skilled workers, and often migrants. Labour migration is crucial to our economies as migrant workers fill the labour and skills gaps that exist in countries. However, migrant workers are susceptible to labour trafficking and exploitation. This is because migrants are often marginalized, have limited access to legal and medical services and lack the protection of family and social networks that locals may have. Migrant workers are often recruited under false promises of good wages and working conditions. Once at their workplace they can have their documents confiscated and may be threatened or coerced to work under bad conditions. Products from exploited migrant workers then get distributed all over the world through the intricate supply chains that exist in this era of globalization.

Despite the difficulty of overseeing complex supply chains, there are plenty of motivations for companies to implement strategies that can fix these problems. Primarily, human trafficking is a crime and companies can face legal penalties if found guilty of forced labour. Additionally, cases of human trafficking can cause severe damage to a brand’s reputation and this can be costly as 30 per cent of a business’ value is attributed to its brand. Conversely, a company that publically aims for a clean and sustainable supply chain may also attract more customers, as a study suggests that 87 per cent of customers are likely to change to brands that are associated with a “higher purpose”.

Consumers are becoming more aware and conscious about the products they buy and are increasingly calling on companies for more transparency in their supply chains. In the United States consumers have filed a number of class action lawsuits against companies for not disclosing that there was forced labour involved in their supply chains. Employees themselves are also starting to file lawsuits against companies. Even if such lawsuits are not successful, it is another motivator for companies to eliminate forced labour from their supply chains.

Cleaning up human trafficking and forced labour in supply chains is unfortunately not a quick and easy fix, because there are so many suppliers and workers involved, often spanning multiple continents. Yet since a series of stories broke about child labour in creating goods for major sports brands in the 1990s, companies seem increasingly motivated to clean up supply chains; a study shows that 54 per cent of Fortune 100 companies have policies in place that target human trafficking and 68 per cent have made a commitment to monitor their supply chains. There are a number of effective solutions that are being implemented, some of which you can read about in our next blog.

Editor’s choice

Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

In 2015 when IOM X was just a few months old we brought together 20 youth leaders from all 10 ASEAN countries in Bangkok for the IOM X ASEAN Youth Forum. The goal was to connect with amazing young people who were passionate about social change and the issue of human trafficking and to share … Continue reading “Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines”

Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

In 2015 when IOM X was just a few months old we brought together 20 youth leaders from all 10 ASEAN countries in Bangkok for the IOM X ASEAN Youth Forum. The goal was to connect with amazing young people who were passionate about social change and the issue of human trafficking and to share … Continue reading “Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines”

Power by

Power by