Creating “No One Should Work This Way”

Sometimes a body of work starts because something sticks with you. An idea. An image. A story. In my case, it was a sentence. Well, several sentences. “You’re a dog. You’re a pig.” “You’re so dumb. You’re worse than a pig.” “Come here, dog. Come here. You are stupid. You are a dog. … You’re a doggy.”

I heard that from three women who were domestic workers, recounting the way they had been treated by their household employer — female employers mostly, in Asia and the Middle East.

I interviewed these women nine years after I had read similar statements in a Human Rights Watch report. And that report was published about a decade after I had first written a newspaper story on a teenager who had gone to work as a maid in the Middle East at age 14 and had been sentenced to death by firing squad for repeatedly stabbing the widower employer who had tried to rape her. Her family was so poor they struggled to feed and obtain medical care for 14 children (six died for lack of care). She had dropped out before finishing primary school to work to help the family.

Between that story and the Human Rights Watch report it seemed things had become worse.

More girls and young women were going abroad to help their family afford the basics of everyday living — food, a roof that doesn’t leak, education, health care. More mothers were leaving just to give their children a better life.

As my work shifted from journalist to report writer and research editor for NGOs and United Nations agencies and back to journalism over a period of twenty years, this issue of girls and women leaving home to find employment in another country repeatedly appeared in my assignments. There were stories for sure of migrant journeys that worked out — at least in the sense that the domestic workers were able to send home some money. Many of them still probably worked slave-like hours and in less than decent conditions. I read stories of domestic workers who were treated with dignity and who flourished. But there were many accounts of women and girls going home not only empty handed but with injured hands. Or worse.

In 2006 I was asked to compile all that had been published on Indonesian domestic workers’ experiences into one document for lawmakers who were considering legislation to better protect domestic workers within the country and abroad. One of reports I included, the report by Human Rights Watch, hit me the hardest. But it was less the stories of women who were beaten or made blind.

Instead, it was the accounts of being called a dog. Or likened to some kind of animal. These words stayed with me. Haunted me actually.

When my life as a migrant journalist reached a point where I could focus on documentary projects and be gone from home for extended time (my son had left for university), I asked a photographer friend, Steve McCurry, whom I had worked with previously on an AIDS assignment, if he wanted to work with me — for free. I had a grant from the International Labour Organization and wanted to stretch it to as many countries as possible. He too thought it an issue that needed to be brought out from behind closed doors.

We went looking for scars. This approach didn’t settle well with some people we asked to help us. But it seemed important to show evidence of the abuse taking place in private. We thought it was necessary to make that evidence public. My second job ever as a young journalist was with LIFE magazine.

There, I learned the power of an image. I hoped that in showing the evidence of abuse, something would stick with lawmakers, advocates, maybe recruitment agents and even employers, and they would be moved to make changes needed to better protect workers.

I also wanted to tell each person’s story. I wanted people to see that these women are mothers and daughters striking out somewhere foreign just to make a better living because they had no or few options at home. They are workers without proper labour protection, like what I am entitled to even living in foreign countries. I know we can’t legislate decency. But we can better hold abusers accountable.

I couldn’t turn away from something I knew was going on far out of view and far from my everyday world. That’s how this project started.

No one should work the way we documented. I want people who could possibly make a difference see our work and agree. Then do something to change that world a little bit.

To view the exhibition photos, read the story of each domestic worker involved, and learn how you can host your own event, visit http://nooneshouldworkthisway.org/

View a video about the project at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XV7R1ZhUYdA

The ‘No One Should Work This Way’ project was undertaken by photographer Steve McCurry and journalist Karen Emmons. This post was written by Karen Emmons.

(English) Editor’s choice

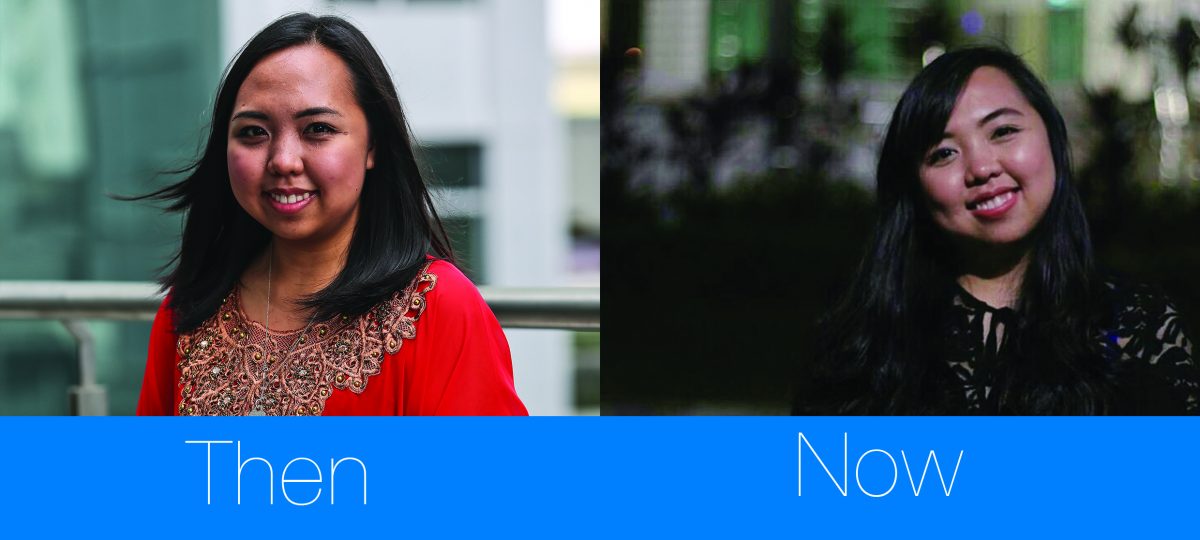

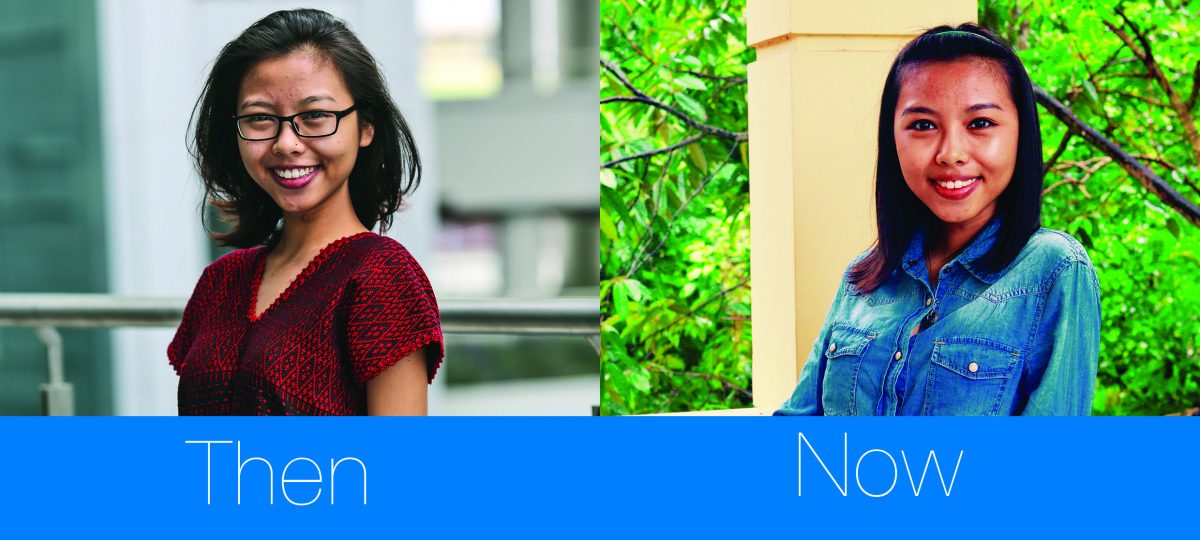

(English) Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

sorry not available!

(English) Where are they now?: Joey, Philippines

sorry not available!